Vinnie Paul: ‘My Life Has Been One Gigantic Comic Book’

The message, unexpected and awful, came late at night, like the previous missive had 14 years prior. December 8, 2004, to be exact. A supremely talented guitarist and first-class person, way too young and vital to die, was gone. In the case of “Dimebag” Darrell Abbott, there was an added weight: he was assassinated, killed on stage doing the thing he loved the most: playing guitar with his band Damageplan, his brother, Vincent Paul Abbott, on drums as always. Dime was 38.

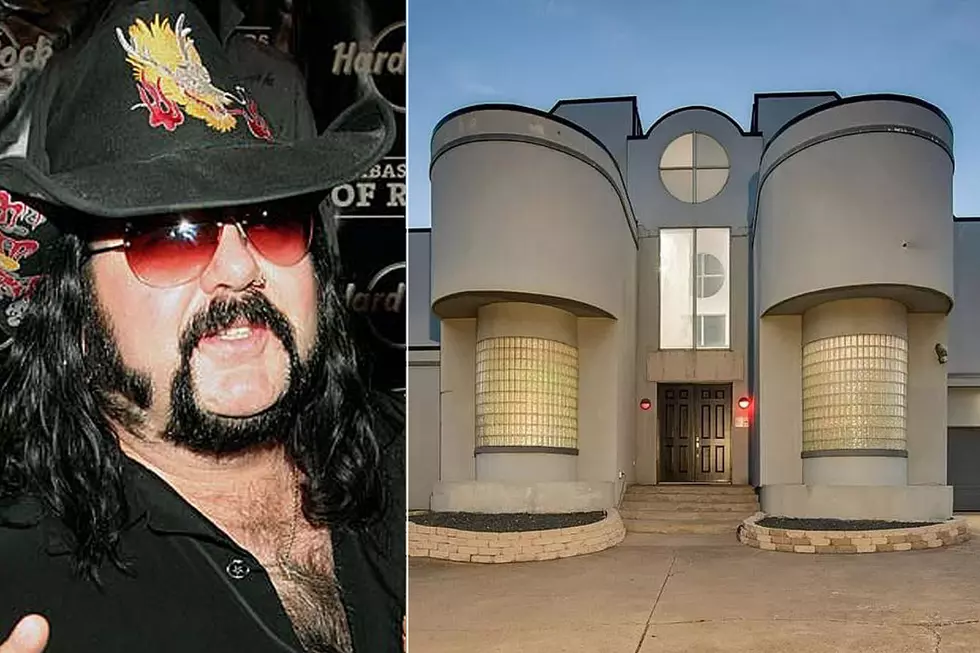

When the notice popped up around midnight on June 22, 2018 -- “Pantera drummer, co-founder Vinnie Paul Dead” -- it was a gut punch, a throwback to that sad night of disbelief more than a decade earlier. Vinnie, bearer of his younger brother’s torch—not only for the last 14 years, but for the entirety of their personal and professional lives—was gone. He was talented, fair, hardworking, stoic, and at 54, he had decades of music and life ahead of him.

My first Pantera memory is a regret: In 1990, as an editor at RIP magazine, the offer came in to send a journalist to Dallas for a launch party for Cowboys From Hell, Pantera’s major-label debut. As a staff editor, I had dibs, but I choose not to go, and sent a journalist, Tom Farrell -- who passed away five years ago -- to represent the magazine and get the scoop. I missed a helluva a party.

In the ensuing years, however, I made up for missing that stellar kick-off, going to numerous gigs -- some, like the Las Vegas end-of-tour show with Type O Negative -- insane and insanely memorable, even through a whiskey and Jagermeister fog. Since the early 1990s, I’ve interviewed singer Phil Anselmo and Vinnie as often as possible, and bassist Rex Brown and Dime less often, for no reason other than scheduling and availabilities. Some conversations were in person, some over the phone. Once, in New York, Anselmo leafed through a boxing magazine while speaking with me; another time he peed during our interview, which, thankfully, was over the phone. Vinnie never gave me less than full attention and respect.

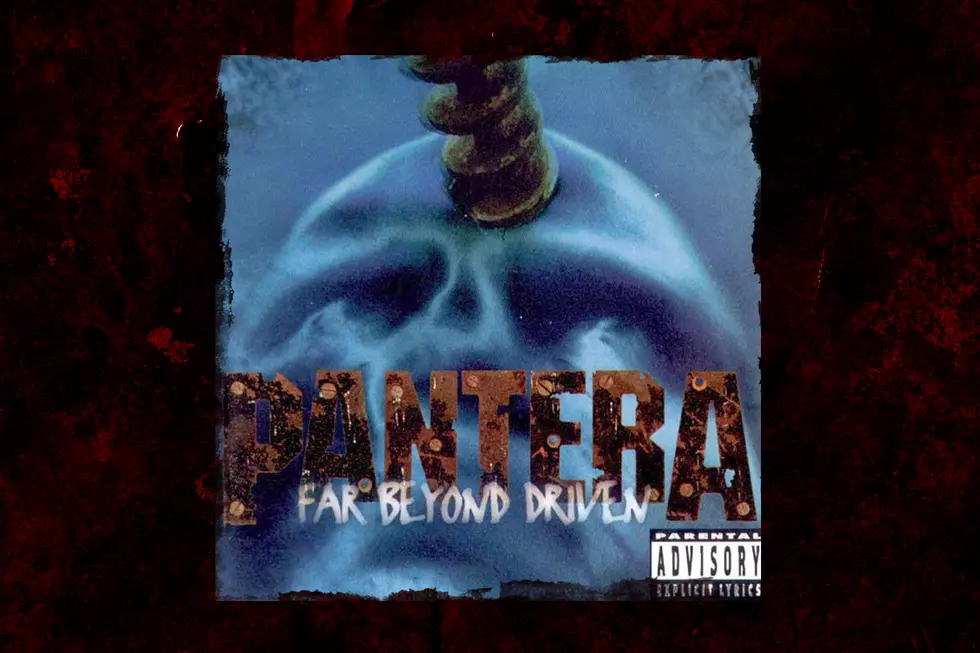

In 1994 I was writing for The Los Angeles Times, who for some reason, had deigned to cover metal, and they hired me to do much of that coverage. When Far Beyond Driven debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts, I wrote that the album was “not for the faint of ear,” calling it “truly merciless” and “ferocious and dynamic.” That’s exactly what I want from my metal, and why Pantera was and remains one of my Top 3 metal bands. That, and the Texas/Southern bent that permeated their manners and music, especially well displayed in Rebel Meets Rebel, the country-metal project the Brothers Abbott (along with Brown) did with David Allan Coe.

Rebel Meets Rebel, "Rebel Meets Rebel"

Vinnie, though I cannot claim to have any insider knowledge, always struck me as a man’s man, a stoic, upstanding Clint Eastwood type—but unlike those loner heroes, Vinnie always had his sidekick in Dime. The early dynamic of Pantera could be difficult, as one-time singer Terry Glaze told me. In disagreements, it would often be two against the world—the Abbotts—and in some cases back then, three, when producer/supporter father Jerry Abbott (who has the anguish of having both sons die before him) steered the band. But Pantera was at its musical and personal best when it was four against the world, which it usually was.

My last chat with Vinnie was about two years ago. I had an awesome honor bestowed upon me: I was asked to write the liner notes for the Rhino Records re-issue of their 1996 album, The Great Southern Trendkill. I was to interview Vinnie, Rex, Phil and several label and studio personnel involved with the band during that period. At the appointed time for me to speak Vinnie via phone, I was on the street in the Chelsea area of Manhattan, between other appointments. I tried to find a quiet bench, and conducted my interview there, as kids played around me.

Vinnie said that the making of Trendkill still seemed “very close, very familiar,” and told a tale about the album title. “It was one of the last things that came about, because the record company mistakenly took the title to be 'The Great Southern Trendkillers.' We were behind on the deadline and they almost insisted that we call it that. It was like 'No, it’s called 'The Great Southern fucking Trendkill' and you’re going to change it, that’s just the way it is.’ The record company never really had any influence on us; it was always the four of us and [producer] Terry Date. Any time they tried to enforce us or do something, we were not into it and pretty much against it. I’m sure this record scared them to death, too, but they got it, and the highest it went was number four on Billboard, which our previous was number 1. Still, if you get to Top 10 and you’re a heavy metal band and you don’t have hits on the radio, MTV doesn’t pay attention to you, and mainstream rock doesn’t pay attention, to have that kind of success is pretty huge.”

Trendkill was a very tough album to make—Anselmo recorded in New Orleans, isolated due to drug issues—while the rest of the band worked in Texas, at the newly constructed Chasin’ Jason studios on Dime’s property. The brothers were no angels, but, but they were anti-hard drugs while definitely enjoying their whiskey and pot. Unlike Anselmo, they were not driven by demons. The lyrics to “Suicide Note Pt. 1” didn’t resonate for Vinnie. Still, when talking about the album twenty years later, Vinnie was blunt about the anger toward Anselmo, but circumspect for the posterity of the liner notes: “Nah, I don’t need to paint it as too dark of a time period, but it really was difficult to make the record, do the tour and get through all of it at that point in time.” A true gentleman.

Pantera, "Drag the Waters"

As for industry accolades, Vinnie was also very matter-of-fact: “We were nominated for four Grammys, and never won a single one. We got beat by Rage Against The Machine, Deftones, Soundgarden and somebody else [editor's note: Tool, in 1998], but none of these bands are heavy metal bands, so it was one more thing that signified that the industry wasn’t aware of heavy metal, much less Pantera. That was one thing I wanted to win because my mom; she didn’t really know much else in music, but the Grammys were special to her. I still got the four nominations hanging on the wall in my house to remind me that I never won any of them.”

But the fearsome love from the fans, peers and the unwavering brotherly camaraderie—which they modeled on the Van Halen brothers Alex and Eddie, the heavy hitting, rock-solid drummer and insanely innovative and fast-fingered guitarist— and the seven official Pantera albums featuring Anselmo is a legacy that few can match. No one ever had a bad word to say about Vinnie, and rightfully so. He truly was one of the rare “good ones.” Bereaved messages from musicians from all genres have poured forth—Sebastian Bach cried in a video, Greg Dulli (Afghan Whigs) praised Vinnie’s kindness; magician Criss Angel tweeted that he’d “miss” his Vegas pal; Howard Stern sidekick and fellow drummer Richard Christy rightly called him “the John Bohnam of metal.” Then there was the time in the early ‘90s when I met and hung out with a few members of the nascent Alice in Chains when they were far from a household name. What did they want to do? Watch a Pantera home video that they were featured in. Jerry Cantrell couldn’t have been more excited.

Oh, and that Vegas show and ensuing shenanigans? It’s more than 25 years ago, and still one music biz attendee says “That was the most rock and roll weekend of my life, hands down.” Another remembers, “The show at the Thomas and Mack Center [in Vegas] was the last show of the tour. After which Pantera got banned from the venue because of the toilet papering that Type O did to them as an end of tour prank. Fire hazard.”

One of my memories from that delightfully debauched and very metal weekend: At the MGM Grand Hotel, after the show, the bands and their entourages — label people, journalists, photographers who were all fans -- were hanging around the casino. I remember Vinnie, in boxers and cowboy boots, with his feet propped up on a blackjack table. Also, Vinnie walking through the casino, his hotter-than-hell Penthouse model/girlfriend on his arm. He was a guy who had it all and was enjoying the ride, never copping an attitude other than coolness and kindness.

In the book I co-authored with Jon Wiederhorn, Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal, Vinnie took a look at the big picture, observing, “My life has been one gigantic comic book, and on the other hand it’s been one gigantic book of laurels and amazing accomplishments, and on the other hand it’s been a book full of horror stories. It’s a big book.” And now, sadly, the book is closed.

I feel broken by the passing of such good people who gave the world a musical outlet for angst and pain, ultimately sowing transcendence via their music and attitudes. As the lyrics to “I’m Broken” go: “I wonder if we'll smile in our coffins / While loved ones mourn the day / The absence of our faces / Living, laughing, eyes awake / Is this too much for them to take?” Yes, yes it is. Thank you for everything, Vinnie.

Vinnie Paul's Best Songs: Pantera and Beyond

Vinnie Paul: Pantera and Beyond Playlist

More From Classic Rock 105.1